The pattern of the self is the biggest memory object in the brain. It involves all other memory objects. That means that all the patterns that you have discovered in external stimuli, together with the genetic properties of the brain, make up who you are. All of these memory objects have their own emotional connections, dictating the way in which you value them, and how you respond to them. In this article I am going to argue that the more an external or abstract object, be it static, dynamic or social, is present in the pattern of the self, the more it will be viewed as important. This article is part of a series of articles. As I have said before, I am not a neuroscientist or a psychologist, so take this with a grain of salt.

When a baby has a favorite toy, it takes this toy with it wherever it goes. This means that this toy becomes a big part of the overall pattern in the baby’s memory. The baby goes to the doctor, the toy is there. The baby goes to the zoo, the toy is there. The baby eats breakfast, the toy is there. Because of this, the toy becomes a big part of the memory of the baby. Since the presence of the toy creates micro memories of the toy being present, the understanding of the toy gets wider (as in, it has been involved in many things) as it entangles in all of these other patterns. The toy memory is now part of all these other things as well. If the baby thinks of the doctor, it can associatively open up memories of the toy. If the baby thinks of the zoo, it can associatively open up the memory of the toy. This way, the toy memory object becomes often present in the thread. Therefore, its presence in the memory becomes more and more reinforced. And so do its emotional connections.

But what if the toy is lost? What if, then, the baby has to go to the doctor? Think of the doctor, think of the toy. But the toy is lost. So the doctor makes the baby think of the lost toy. So does the zoo and having breakfast. Because the toy was so entangled with other memory objects, it keeps on popping up in the thread, even after it is lost. The baby therefore really misses the toy. The toy had become more important than any other toy.

The adult male and his car

And so it is with the adult male and his car. He talks to his friends about his car. He drives his car wherever he can, because he likes it. When he is at home, he washes the car and cleans it. He cannot stop thinking about his car. He keeps on making micro memories that relate the car to all other aspects of his life. And because of this, he cannot shut up about his car. The car has become important to the adult male.

The importance of certain external objects to a certain person is, I will speculate, directly related to the amount of entanglement that the memory object representing that external object has with other memory objects of the pattern of the self. The more they are entangled with other memory objects, the more important they will become.

Social entanglement

If you have interacted with another person doing different activities together in different settings, this person becomes entangled with your overall pattern. You will start to associate this person with these activities and settings and their underlying memory objects. In other words, the person becomes socially entangled with you.

People with whom we are socially entangled are important to us.

With important, I don’t mean that they are an authority to us. What I mean is that we think about them a lot and therefore also want to talk about them a lot. So if we are walking in a street and see someone wear a certain shirt, we think: “hey, such and such always wear a shirt like that”. Or when we hear a certain type of joke, we think: “that’s the type of joke such and such would make”.

This importance could be both positive and negative. If someone is a victim of a crime, then the perpetrator will become important in the mind of the victim. They have violated them and therefore are a great threat to them. They have a lot of anxiety connected to this one person. Because of the anxiety, the victim either keeps on thinking about the event, thereby reinforcing the perpetrator in the overall pattern, or tries to steer away from these thoughts. In the last case, the victim will also start to build up a big entanglement in the overall pattern. This will happen in the form of: “I cannot hear this type of music because it reminds me of them, and therefore I have to walk away”, or, “when I smell that, that triggers a recognition response of them, so I cannot go to the place with the smell”. In this way, the perpetrator will still socially entangle with their victim. So, also the perpetrator and the victim are socially entangled with each other. Important does not mean good.

Social entanglement schema

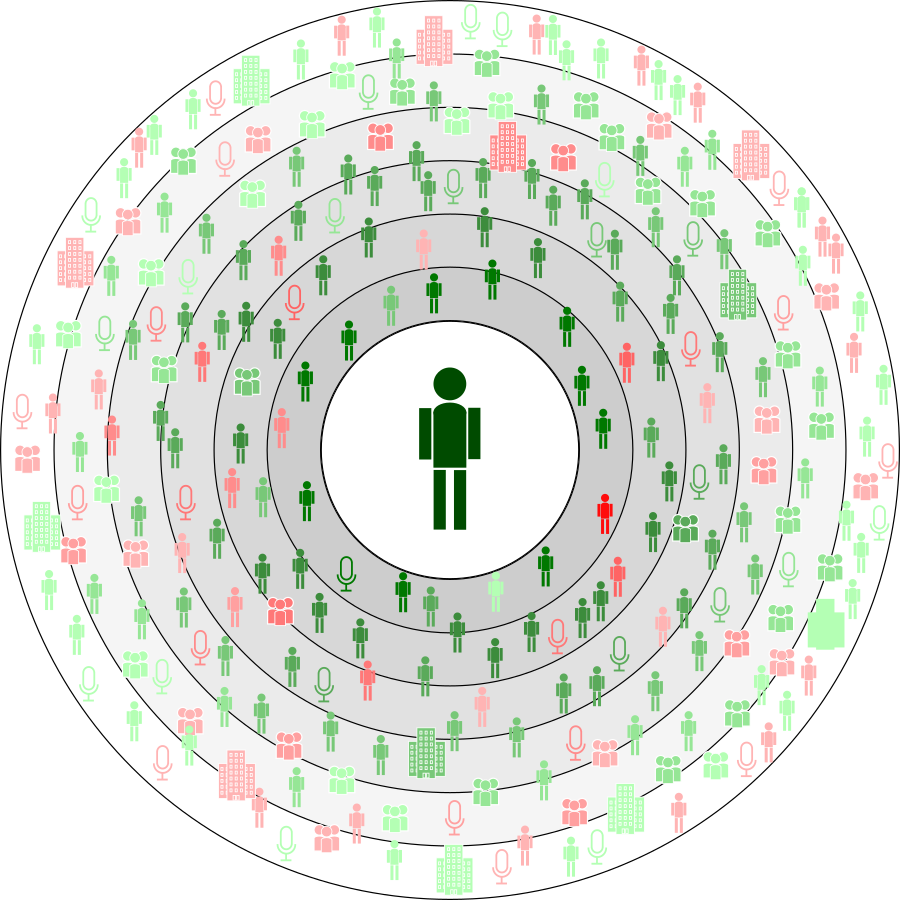

We can now map out the importance that some people play in the overall pattern of the self. To what degree are the people surrounding the self entangled with the other memory objects in its pattern. Now, it would be pretty difficult to accurately measure this with someone, but the result would look something like the simplified image below.

The above depicted image depicts a hypothetical example of social entanglement of an average human brain. The circles represent the degree to which a person has been entangled with this brain. So the closer to the self, the bigger the chunk of memory that they entangle with. So in the inner circles are your family, your closest fiends, or maybe a coworker you work with a lot. They don’t necessarily have to be emotionally valued highly. They can be, but they don’t have to be. As long as enough patterns have been discovered in the other to make them become a big part of our own pattern, we start to recognize their patterns a lot in other patterns we see, and therefore, we start thinking about them.

The color of the icon in the diagram represents the net emotional bond that the brain has with these people. This net value is the result of all the positive and negative things that are associated with that person. So for instance, someone likes going to a football game with someone, but they hate the way they drive. In that case, there probably is a net positive, unless the other is a really terrible driver.

Since these emotional bonds are an accumulation of all memory objects associated with this person, only people that are entangled a lot can have strong emotional bonds. But they don’t have to. Emotional bonds can be neutral.

In the image, the little person represents a single individual. The big one in the center is the self. In this case, the self is seen as good. The individuals that are surrounding the self are each valued in an individual way. They are seen as individuals. They don’t have to be known by name, as long as they are seen as an individual, like the cashier at the supermarket that you like to talk to, or something like that. You don’t know their name, but they are an individual in your head.

The icon of three people represents a group. When you drive by a gym, and you see people go inside, but you don’t know any of them, they are “people who go to gyms”. These are classified in the brain as a single group with the same characteristics. But also the people at work that you don’t interact with, like the people working on a different floor, are kind of seen as a group with the characteristics of a person. There are also negative groups, like with criminals, whom people often think are all alike. Also, minorities are frequently seen in this way.

The buildings icon represents a society of people, like Africans or Asians or Muslims. People tend to attribute stereotypical behavior to these groups.

In a way, the last two groups are based on emotional weighing of their local collective mind. What this is, I will explain in the next article.

The microphone icon represents parasocial entanglement with an individual, a network, or another group of people that we have one way social interactions with. These interactions change the pattern of the recipient, but not of the sender. These can also be valued in many ways and can be entangled a lot or a little, depending on the interaction that has been had with this parasocial sender.

So why do humans group people together and attribute general characteristics to these groups? Let’s go to Uganda, where the Ngogo chimpanzees live.

Ngogo Chimpanzees

A while ago, I watched this documentary called Rise of the warrior apes. This is a documentary about a community of chimpanzees in the jungle of Uganda. It is a very beautiful documentary about a lot of chimpanzee behavior that I could write about for hours, but I want to focus on one thing in the documentary.

In the documentary, they mentioned that the community of chimpanzees at Ngogo was rather large, and that this caused a lot of friction. I think that I can explain what happened by adopting the idea of social entanglement.

Let’s follow the day-to-day life of a male chimpanzee. He socializes with the other chimpanzees. He grooms them, he eats with them, hunts with them, and so on. They therefore become part of each other’s pattern of the self. They become socially entangled. Then the chimpanzee leaves and socializes with some other chimp. Together they might hunt for monkeys. They then socially entangle with each other. Because they are entangled, they understand each other’s pattern. They are kind of in sync with each other. They can gauge their feelings to judge the other and kind of predict their behavior. These feelings in the chimpanzee will correlate with the past experiences that they have had together. In this way, each chimpanzee tries to socially entangle at least a bit with the other. They know each other. They have become part of each other.

Now the community grows, but the amount of time in a day stays the same. Our chimp does not have time to socialize with everyone, and plasticity doesn’t last forever, so our chimp has a maximum amount of other chimps it can assess. Now let’s say that our chimp is grooming one of his friends and sees a chimp that he doesn’t recognize. Our chimp doesn’t know if the unknown chimp is part of the community, because, either our chimp hasn’t socialized with it, or it has forgotten. Either way, this unknown chimp is not stored in our chimp’s memory. Let’s say that the unknown chimp actually is socially entangled with known chimps from our chimp’s community, and is therefore part of the community. Let’ also say the unknown chimp is young and no match for our chimp. Our chimp might be curious to get to know the unknown chimp, but he is busy socializing with another one. Our chimp can try to get to know the unknown chimp, but then he will lose entanglement with his current friend. He decides to ignore the unknown chimp.

Now the group becomes even bigger. It has become a hodgepodge of social entanglement. Some parts of the group are entangled with some other groups in the community, but not with a third group. Some individuals know some, but not others. The group has just grown too big for all of its members to socially entangle with all the other ones. Our chimp sees the unknown chimp again. The unknown chimp has grown up and now has three friends. This is becoming a threat to our chimp. He doesn’t know this group and cannot predict their behavior. They have become a potential danger to our chimp. He needs help. He calls for help in the same way he would if he saw an enemy community. Threat! Other chimps come to the rescue. They are also not socially entangled with this part of the community. They yell at each other and then split. A civil war is brewing.

After the documentary, the civil war actually happened. The Ngogo chimp community split into multiple different communities.

Our chimp’s identity

Our chimp had time constraints on whom he could interact with. Sure, he could interact with the unknown chimps, but then he could no longer interact as much with the other chimpanzees, and he would lose social entanglement with others. Then he would be in the same situation as with the unknown chimp, only with other chimps. He simply doesn’t have time to socialize with all.

And so our chimp can only interact with so many chimps. These chimps will serve as a guide to our chimp. He can recognize their patterns and judge them. Does he get good or bad feelings associated with these recognized patterns in other chimps’ behavior? This ability to judge them, leads to trust and recognition, because our chimp can make a prediction of behavior from chimps he knows.

What is important in this is that, not only the way in which our chimp sees the community, but also the way the community perceives and treats him, are dictated by social entanglement. So even if our chimp has a special brain and could socially entangle with more chimps than usual, he would still have to deal with a community that does not have this ability.

The group’s identity becomes our chimp’s identity

So our chimp has to make his communities patterns his patterns. He recognizes these patterns all the time, and therefore they pave plasticity in his brain. He becomes his community. But since his community is also influenced by him, they become him.

And so we see that our chimp’s identity leans on social entanglement with others. He recognizes their patterns and therefore absorbs them into his own pattern. But the others also do this with him. So our chimp’s identity leans on the identity of those who lean on him. This is very similar to memory objects having to be averages of multiple things that are interconnected. The chimp’s identity follows the same pattern. It can only exist relative to another chimp’s identity.

These principles also apply to humans.

Heuristics

Because our Ngogo chimp didn’t know the other chimps from his community, he had to make a quick assessment of the situation. He cannot interact with them because of time constraints, so he makes a quick assessment of strength. When our chimp first encountered the young unknown chimp, he was in the presence of a friend. But when he encountered the unknown chimp the second time, he was outnumbered. This would have triggered a prediction. Multiple chimps can beat up one. Our chimp has experienced this, maybe even first hand, and knows this. This realization that he is in this tough spot makes him anxious. So he starts to call for help.

Since the chimp has not socialized with the group of unknown chimps, he can not assess if they pose a threat to our chimp. So, what our chimp does, is make an assumption that the other chimps are a threat to him. This way, he can be sure that he stays as safe as possible by using the better-safe-than-sorry method. This is a heuristic, a rule of thumb. Our chimp doesn’t know the other chimps. He does not know that he is indirectly socially entangled with them. Therefore, the safest way of dealing with them is assuming that they are a threat.

This problem arises because the group of chimps is simply too big. It is impossible for all chimps to socialize with all other chimps in a community as big as the Ngogo community was. Therefore, a rift was bound to happen.

Humans and (incorrect) heuristics

Human communities are many times bigger than the Ngogo community. I think this is only possible with language. Language makes it that we can indirectly socially entangle with each other. Other people can entangle with our pattern of the self, even when we don’t know them. Others can tell us about them with the use of language.

This does not mean that humans do not need heuristics to understand our huge communities. And it certainly doesn’t mean that these heuristics cannot be incorrect.

Human beings need to use heuristics to understand all the people around us. We group them together in our minds. When you work in a certain building where the bathroom on your floor is very clean, but you notice that the bathroom on the second floor is a mess, then you tend to think that “the people on the second floor” are slobs. Those people working on the second floor could be, in fact, not all slobs. There could be coincidentally a couple of slobs more in that group.

What seems to be happening here is that we encounter one result of many individuals together. Since the actions of a group of people together will lead to one result (like a mess in the bathroom), it is only one pattern that has to be discovered. This pattern is then linked not to an individual, but to a group. Since the group shows this behavior, all people in the group show the behavior, at least in our minds. Of course, in actuality, there are plenty of people on the second floor who are not slobs. But because they do not appear in the result pattern, they are ignored.

And so it is with our media. People discover certain patterns in groups of people who have equal characteristics in some irrelevant way. African Americans are seen as lazy and criminal, and Arabs are violent terrorists. This characterization of groups of people is the result of the media watcher trying to put a simple logic behind what they see, so that they can easily remember it and use it to predict future behavior coming from society. They do not recognize that the people that they see on television, that they have grouped together in their mind to remember “their” pattern, are, in fact, individuals. They might, but also might not, show this behavior. This stereotyping can cause problems.

If a young African American man has gone through High School and College and is looking for a job, many will still hold him collectively responsible for what other African Americans do. When you point out to certain people that a lot of research has been done that proves that job applications with African American names do worse in job application processes, an often heard response is that they should just act normally, and then they will be treated differently. However, the young African American who did nothing wrong is not a “they”. He is a he. He did nothing wrong. And yet, because of his skin color, he is held collectively responsible. They cause problems.

These incorrect heuristics cause a ton of problems. I will write about them in a later article in this series about experience trapping.

Parasocial entanglement

When people listen to others, for instance on TV or on the internet, they get influenced by the other. But the other does not even know about the first. The social entanglement is a one way street. I want to call this parasocial entanglement. I want to call the famous person who gets entangled in the minds of others the parasocial sender, and the others are the parasocial receivers.

We are all parasocially entangled with others. For our brain it does not matter, however, if the entanglement is the result of social interaction or of one way street listening. The parasocially entangled become just as important to us as the socially entangled. That is why if you hear about someone that you have never heard of dying in an accident somewhere, you think: “Bummer for them!” and then forget about it. But when someone that you have parasocially entangled with dies in an accident, like a TV show host of a program you often watch, then you feel as if someone close to you died, even though you have never met the parasocial sender and the parasocial sender didn’t even know you. If you died in an accident, they would have thought: “Bummer for them!”.

Not only negative emotions from experiences like death are introjected by the receivers, but also positive ones. If a parasocial sender has a new puppy, tons of people want to feel the excitement that the sender feels. Suddenly even this puppy becomes important. And the more people parasocially entangle with a person in this way, the more important that person becomes in the minds of those people. This elevates the person’s status.

Status is the total amount of parasocial entanglement someone has within the community they reside in.

Status is important for people with certain professions. They need to be important in the minds of people to sell them records, movies, TV shows, and so on. Status is what all parasocial senders strive for.

Social entanglement and the political spectrum

The political spectrum seems to be heavily influenced by the degree in which people see their social entanglement schema as an objectively true evaluation of people’s worth. The more people think that people outside their individual social entanglement circles are equal to them in society, the more left wing people are. Left wing people usually care more for poor people, for minorities, for people abroad, and in time of war, they have more empathy for the enemy. The more right wing someone is, the more they will see the people in the out-group as a statistic. This brings us to authoritarianism.

Social entanglement, authoritarianism, and war

We all love our family members. To us, they are the most special family members in the words. We are socially entangled with them to a high degree, and they with us, and are therefore important to us. Most people understand that this does not mean that our family members are objectively better and more important than other people’s family members. We recognize that they are important to us.

Authoritarian people are not like that. They think that their socially entangled group is objectively worth more. There are far more authoritarian people than you might think. Allow me to explain.

The attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11th 2001 were shocking to all in the West. Here in Europe, it was in the news for months. In the US, it was even more, of course. On top of that, because of a lot of cultural exchange and other forms of social entanglement before nine-eleven, the people in Europe already cared a lot about the people in the US. We have a lot of emotional connections in our brains connected to memory objects that represent and are entangled with the US. So this event was very shocking to us here in Europe. In China, people are socially entangled with people in China and people in nearby countries. They don’t really know people in the US. They don’t see them on TV or on their internet. When they heard about nine-eleven, their response was very different. For many of them, this event was, and still is, just a statistic. This is not to say that they approve of it, or are morally ambivalent. They just have no emotional connection to the event. Since they do not have emotional connections in their heads with the US, other than a couple of stereotypical ones, and there is almost no social entanglement, they just don’t care as much.

The same happened here. If in Europe you want to talk about victims in some African country that we are not socially entangled with, people from the right wing tend to respond with a remark that they don’t care. I would not expect them to. Like the people in China and nine-eleven, they are not socially entangled with them. For them, these people are just a statistic. But also people on the left don’t really care on an emotional level, unless they have somehow socially entangled with them. If they haven’t, they will probably think that this is terrible for those people. They don’t feel the terribleness. It is just a statement of fact. They will forget the next day, because there is no real emotional attachment. I am not trying to scold these left wing people either. We are all like this. I am like this.

The problem arises when one group starts to demand that the other has to care as much about their socially entangled group as they do. For instance: “The people in China are bad people, because they don’t care about nine-eleven as we do!”. Of course they don’t! They don’t have the emotional connections. They are like us. They care about their own socially entangled group, not ours. Their right-wingers don’t care about us at all, and their left-wingers only on a factual basis. And yet, some people demand of others that they value their in-group as much as they do. These people are authoritarian.

When authoritarian people get power, it creates war.

Authoritarians value the people that they are socially entangled with as objectively more important. They are not just important to them, they should be important to all. An authoritarian, for instance, thinks that when they kill many children with bombs, because they are not socially entangled with them, they are just statistics. To them, they are not real people. When the reverse happens, the killings are perceived by the authoritarian the worst crime ever committed.

But on the enemy side of the conflict there are also authoritarian people. They think that only their victims are real people. They have no qualms about killing people outside their socially entangled group. They strike back. It is war.

Since this article is long enough as it is, and I could write endlessly about war, I will end it here. No doubt this topic will come back in later articles.

Empathy

When you see someone fall from a ladder, you recognize this pattern. You might not have fallen from a ladder specifically, but in your lifetime you have fallen. You know what it feels like. So when you recognize the pattern in the external stimulus, you will also get that feeling. Someone who, by some miraculous way, has never fallen ever in their lives, cannot have empathy for someone who falls.

When people are socially entangled with each other, they start to copy each other’s patterns. They start to see and feel things in similar ways, depending on the social entanglement. In a way, you are them, and therefore you can feel for them. If you then see such a person in trouble, you can more easily reproduce the feelings that they must have. Since you care about them, you also start to feel troubled. So your thread starts to make predictions as if it was you who was in trouble. This basically seems to be what empathy is.

All empathy is limited to the experiences that the empathy feeler has experienced in their lifetime. People who have never been in a war can never have real empathy for someone who has been. They can think that they do, but they compare the emotions to the worst in their own memory. This is not enough. It is therefore effective when the news shows real footage of terrible things. This way, external stimuli guide your anxiety. You can now feel better what it must feel like to be in the middle of a war. But it is still not the same. Social entanglement with the victims of war also makes us show more empathy. Without this entanglement, our empathy is just a statement of fact. “How terrible for the people in Rwanda!”. And then it is forgotten.

This last thing I would call rational empathy. It is an empathy that is not based on direct emotional connections with the person for whom there is empathy, but on an understanding that, even though we haven’t seen the people in Rwanda, we can kind of understand what they must have gone through. This leads to a realization that we must feel some empathy for them. This empathy will not entangle with the pattern of the self that much, so it will not be accessed very often in the future. It will be quickly forgotten.

Projective identification

When humans interact with each other, they try to discover each other’s pattern. With pattern, I mean how they behave. So what work do they do, what hobbies do they have, but also are they quick to anger, or are they nosy, and so on. We want to recognize these social patterns so that we can predict their behavior in the future. But ultimately, by trying to discover these social patterns in their behavior, what we are actually doing is trying to understand the pattern of the self, the actual plasticity pattern in the memory, of the other.

Now a strange thing occurs. Because we need to understand the patterns of the other, in both senses of that word, we need to grow them in the form of plasticity in our own heads. Remember, all patterns recognized become part of the greater pattern and are reused. So if you understand someone else’s pattern, you kind of become their pattern.

I want to take a pause for a second, and I want you to understand that his is a very important part of human interaction. If you understand someone else’s pattern, you become them a bit. I would argue that this has to be true, because any pattern you discover becomes part of your overall pattern. It will be reused in other ways. You will discover patterns that the other discovered and told you, for instance.

In psychology, there is a term called projective identification. I am not a psychologist, so I am not the person who should be explaining this, but I am going to try any way. As I understand it, projective identification is when one person projects unwanted behavior of the self onto another. This other person then introjects this. So for instance, a work place bully calls a colleague a moron all the time (the projection) and the colleague start to self identify as the moron of the office, in the form of: “You know me. I can be such an idiot” (the introjection).

Though I will acknowledge that this behavior is most definitely a thing, I want to stretch the definition a lot more. Allow me to explain.

When years ago I first encounter the term projective identification on some website, it explained it in the following way. Supposedly you encounter someone you haven’t seen in a long while. That person asks if you gained weight. You know that you actually lost a bit of weight, so you respond negatively. And yet, this question has also been stored in the memory. You don’t think about it anymore, until that evening. You are looking in the mirror, and you cannot help but think, does this shirt make me look fat? You look at yourself from the side and wonder why that person said this. This person has crept into your mind.

Because I think that all social patterns are discovered in other humans their behavior, I think that all of your own behavioral patterns are the result of projective identification in this sense. Everything that people say to us that we focus on will create micro memories. These micro memories will create increased plasticity. There is no way around it. It will influence you. That does not mean that it controls you. So, the other person in my example cannot indoctrinate you into believing that you gained weight. And yet it has controlled you at some level. It gave you a bit of worry about something that would not have existed if you hadn’t met the other person. And so it goes with anything someone says to you. It will not control you, but it will influence you.

Before we go…

Social entanglement plays an important part in explaining the behavior of humans. The valuing of other humans and the way in which we then treat them has great impact on society. Understanding its workings is of great importance to societies that want to go forward and that want to prevent crime and war.

Now, on to the next article. It is about the collective mind and experience.